- 4 min read

Updated: Dec 31, 2024

The dance floor has long been a crucible of cultural expression, identity exploration, and social interaction. Far from being merely a site of entertainment, it is a microcosm of society—a space where political, cultural, and interpersonal dynamics play out in real-time. This essay examines the history and politics of the dance floor, exploring its evolution, its role in queer, heterosexual, and racialized experiences, and its function as a stage for both liberation and constraint. By delving into themes such as “bumping culture,” metaphorical masks, and identity projection, I aim to unpack the profound complexities of this shared space.

The origins of the dance floor date back to early communal and ritual dances, where movements often carried religious or social significance. During the Renaissance, European aristocracy formalized the practice through grand ballrooms, where masquerades became a staple. These events allowed participants to don literal masks, disguising their identities and, momentarily, subverting societal hierarchies.

By the 20th century, jazz clubs in Harlem offered a new kind of dance floor, one that became a haven for African Americans and an arena for racial integration, albeit fraught with tension. Later, disco emerged in the 1970s, fueled by queer communities seeking refuge from societal oppression. As Clare Croft notes in Queer Dance: Meanings and Makings, these spaces were not just for dancing but for forging identities and building solidarity within marginalized groups. Today, dance floors range from underground raves to exclusive club spaces, each shaped by its cultural moment.

The dance floor is a site where diverse interpersonal dynamics unfold. For queer individuals, the dance floor has historically served as a sanctuary. In the 1970s, disco clubs such as Studio 54 became iconic for their acceptance of LGBTQ+ patrons, offering a rare space for visibility and freedom. These spaces are integral to what Judith Butler describes as “bodies in alliance,” where marginalized identities claim visibility in public domains.

Heterosexual interactions, often laden with traditional courtship rituals, reveal gendered power dynamics. Men typically initiate contact, reflecting broader societal norms. This behavior underscores Sherry Ortner’s analysis in Gender and Power in Affluent America, where social rituals on the dance floor mirror the broader power structures of heterosexuality.

Racialized experiences, on the other hand, expose how exclusionary practices operate within dance spaces. From the segregation of jazz clubs to the marginalization of Black music genres like house and techno, racial dynamics on the dance floor are fraught with both tension and resistance. Rashad Shabazz’s Spatializing Blackness highlights how Black dance spaces serve as both sanctuaries and sites of political struggle.

“Bumping culture”—the inadvertent collisions and negotiated interactions on crowded dance floors—offers a microcosm of urban social life. These moments of physical contact can serve as opportunities for connection or conflict. As Elijah Anderson’s The Cosmopolitan Canopy suggests, public spaces like dance floors offer a unique setting for encountering the “other,” fostering a temporary suspension of societal divisions.

However, these encounters are not always equitable. Studies on crowd behavior reveal that women and marginalized groups often navigate these spaces with heightened vigilance, balancing the freedom to express themselves with concerns for safety. This dynamic underscores how dance floors simultaneously embody liberation and constraint.

The history of masquerades provides a lens through which to examine the metaphorical masks people wear on the dance floor. Originating in the 16th century, masquerade balls allowed participants to explore identities and roles outside societal norms. This tradition persists metaphorically in contemporary dance spaces, where individuals perform versions of themselves—sometimes exaggerated, sometimes concealed.

Queer individuals, for instance, may perform hyper-masculinity or femininity to align with subcultural expectations, while others use the anonymity of the dance floor to explore aspects of their identity they cannot express elsewhere. Similarly, assumptions of sexual orientation and gender often arise through body language and dance styles, illustrating how identities are both projected and interpreted.

The dance floor is as much about being seen as it is about self-expression. José Esteban Muñoz, in Cruising Utopia, argues that queer spaces like dance floors offer a glimpse of a more inclusive future, where marginalized identities can exist freely. Yet, this visibility is not without its challenges. The erasure of certain groups—whether due to racial, gender, or socioeconomic factors—reveals the limits of inclusivity within these spaces.

For example, the gentrification of formerly queer or Black dance venues often leads to the exclusion of the very communities that created them. This tension highlights the dance floor’s dual role as a site of both community and conflict.

As we move into an era of increasing digital interaction, the physicality of the dance floor remains a vital space for human connection. The politics of the dance floor—its potential for liberation, its constraints, and its ability to reflect broader societal dynamics—will continue to evolve. By understanding its history and dynamics, we can envision a future where dance floors become even more inclusive spaces for cultural expression and identity exploration.

Works Cited

Anderson, Elijah. The Cosmopolitan Canopy: Race and Civility in Everyday Life. W. W. Norton & Company, 2012.

Butler, Judith. “Bodies in Alliance and the Politics of the Street.” Europe Now Journal, 2011.

Croft, Clare. Queer Dance: Meanings and Makings. Oxford University Press, 2017.

Ehrenreich, Barbara. Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy. Metropolitan Books, 2006.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. NYU Press, 2009.

Ortner, Sherry. Gender and Power in Affluent America. Princeton University Press, 1996.

Shabazz, Rashad. Spatializing Blackness: Architectures of Confinement and Black Masculinity in Chicago. University of Illinois Press, 2015.

On November 19, 2024 I was asked to guest lecture the Art History & Culture 200 course at Emily Carr University of Art & Design in Vancouver, BC. The following is a transcript of that lecture in which I look back at the past 100 years of art history to speculate on what the next 100 years will look like.

I am sharing this via my website as I want to note, in the future, if any of my speculations become reality.

Recently, my roommate came home and told me about his 102-year-old friend who recently passed away. This conversation made me reflect on what it means to have lived for over a century—the incredible changes someone born almost 100 years ago would have witnessed. To be a centenarian in the 2020s means they were born between World War I and World War II, representing, in some ways, the love and resilience that brought people together to birth new generations with the hope and aspirations that they would have a better life and learn the lessons of the past. A belief that each new child would carry forward these lessons, using them not to repeat history but to build a better future for themselves, their family, and society as a whole.

To reach 100 years today means there’s hardly room for a hundred candles on a cake. Each candle represents one year of a life, but just as we can’t fit all 100 candles on a cake, our minds struggle to grasp the true scope of a hundred years. It’s as if our memory, like that cake, only has room for so much. We end up with a shortened, simplified sense of history, barely able to hold onto the major moments that have shaped us.

To be a centenarian in the 2020s also means having seen progress in terms of liberation – equal rithts for women, gay liberation, civil rights and protections agasint discrimination and violence. And yet, these centenarians, who bear the scars of past traumas, have also seen the painful repetition of history. Despite strides toward equality, the cycles of oppression, prejudice, and violence persist, resurfacing in new forms. The progress they celebrated in their youth now seems fragile, as issues like neo-fascism, systemic racism, and threats to democracy continue to challenge society. In many ways, their lives are a testament to both the resilience of the human spirit and the sobering reality that liberation must be continually defended, reimagined, and fought for by each new generation.

What does it mean to be 100 years old in 2020? It means growing up celebrating artists like Picasso, along with other figures in the established canon of art history of the 20th century. It also means perhaps only barely encountering figures like Frida Kahlo or Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, Alma Thomas, and Molly Lamb Bombak. For decades, Picasso was heralded as one of the century’s greatest artists. Yet, as we reflect now, his work is undeniably shaped by a male gaze, rife with the objectification of women, cultural appropriation, and what we’d now see as racist and misogynistic undertones.

So, what does it mean to reach 100? Or perhaps more importantly, what have we forgotten in those hundred years?

Just as it’s difficult to picture a hundred candles on one cake, we tend to forget what has passed. Within a hundred years, there may be two, maybe three generations of people in one’s family. And in the span of those generations, there’s so much room for things to slip away, for perspectives to be lost, for histories to be forgotten. Leading, for many of us, to unknowingly repeat the same patterns of generations past. Ironically, in our relentless pursuit of progress, we risk leaving behind pieces of our past, fragments of knowledge that may hold lessons we could still learn from today.

And so, I’d like to present to you a hypothetical speculative performance lecture. Let’s imagine that it’s not 2024, but in fact, it’s 2124. One hundred years from now. Let’s imagine that in your seat, are your grand children. Two familial generations from now. And, perhaps, let’s imagine that I am not Kevin, a TA in your Art History class, but in fact, some hybrid human-android. Perhaps a third or fourth generation of Ai-Da (1), an AI robot artist who recently sold a painting of Alan Turing and his code breaking machine as the most expensive art work eve to sold by a humanoid. Let us collectively imagine that they are in fact lecturing to you in 2124. Let’s imagine that now:

Good afternoon, students. Today, we reflect on what it was like to live one hundread years ago in the 2020s.—a decade marked by what art historians now call “Techno-Modernism.”(2)

In Techno-Modernism, art didn’t merely reflect life; it refracted, distorted, and downright mocked it. The techno-modernist artist played with reality and illusion, remixing it as casually as one would change a filter on a photo app. Like Dadaists and Surrealists a century before them, these artists confronted chaos with equal chaos—except now, the tools had shifted from paintbrushes to algorithms. Instead of playing with scissors and magazines to create collages, artists used neural networks and artificial intelligence.

Let’s explore three particularly insightful works from the 1920s and examine how their themes echoed in the 2020s era of Techno-Modernism.

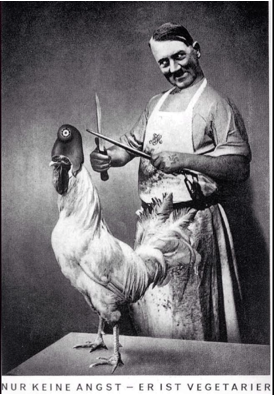

John Heartfield’s “Have No Fear, He’s a Vegetarian”(1936)

John Heartfield’s photomontage, “Have No Fear, He’s a Vegetarian” (1936), which depicts Hitler holding a butcher’s cleaver—a so-called vegetarian who was anything but gentle on humanity—feels prophetic at the time not only for the soon-to-initiate WWII but also for the later rise of techno-feudalism. In the 2020s, we could repurpose this image to depict a future U.S. president, Elon Musk, who was elected in 2036, perhaps holding a rocket while extending his hand to those stricken by poverty, and with the title “Have No fear, He’s a Progressive”. This piece captures an absurdity that was real in both the 1920s/30s and the 2020s/30s: the rise of neo-fascism, now cloaked in the language of “benevolent tech.” Figures like Musk, who ran his successful 2036 political campaign as a “savior” of humanity, launched rockets that resembled phallic monuments for the elite rather than instruments of change to address poverty, homelessness and the rising food shortage.

In Techno-Modernism of the 2020s, billionaires touted “solutions” for poverty, climate change, and even space migration—proposals as surreal as Heartfield’s image of Hitler clutching a butcher’s cleaver. Tech moguls promised liberation while slowly, subtly, but surely taking control over every aspect of life, reducing people to “users,” behaviors to data points, and thoughts to trends. This era marked the rise of what later became known as Techno-Feudalism, where those who controlled behavior (through data sets from online users on social media platroms such as Facebook, Instagram, X and Tik Tok) controlled the economy. Many saw eerie parallels to Italy’s early 20th-century Futurism, with its embrace of technology, nationalism, and fascist ideologies.

Marcel Duchamp’s “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even” (1915-23)

Ah, Duchamp. An early 20ths century artist who knew that art was not something passive, not a precious object in isolation, but something to be questioned, and even laughed at. “The Fountain” is nothing if not an exploration of absurdity and of engagement between creator and audience. Duchamp suggested that art was incomplete without two people—the artist and the viewer. He mocked art’s “sacred” status, something that in the 21st scenturey was turned upside-down by social media.

Art in the 2020s, was participatory in a way that Duchamp could only dream of. The gatekeepers of the art world—the curators and programming committess, who once decided what was worthy of public attention—had been, in many ways, bypassed. Anyone with an internet connection could create and share their work directly with an audience, without the need for approval or validation from a traditional curatorial committee. Art had become democratized, with social media platforms enabling instant and often global access to audiences.

This open access had transformed art from something precious and elite into something casual, fleeting, and interactive. The lines between artist and audience became blurred, as viewers become participants in the works itself. They “like,” share, remix, and even critique the work in real time, shaping its reception and impact immediately. This type of interaction is the essence of what Duchamp envisioned: art that is alive, constantly evolving, and completed by its engagement with the public.

Yet, there’s a new layer of absurdity in this techno-modernist form of participatory art. Duchamp may have dreamed of a more open understanding of art, but he likely could not have anticipated the overwhelming, relentless cycle of content creation in the digital age of the early 21st century. Art had become content, and creators were in constant competition for attention in a crowded, algorithm-driven landscape. The need to “perform” for an audience has intensified, as artists tailor their work not only for personal expression but for likes, shares, and follows—metrics that determined visibility and success. In a way, the sacred status Duchamp mocked had been replaced by something equally hollow: the “sacred” status of virality, where value is measured by reach rather than depth.

Art, once confined to galleries and museums, now lived and died on the screen, its value was determined by engagement statistics and audience reactions. The sacred art object, once untouchable, was then endlessly scrollable, remixable, and disposable. And while this participatory culture fulfills Duchamp’s vision of art completed by the audience, it also raises questions he might never have considered: What happens when art is no longer something we encounter in rare, intentional moments, but something we consume mindlessly in an endless feed? How does art retain meaning when it must constantly perform for an audience that has the power to swipe it away?

In the end, the world of techno-modernist social media art may have delivered on Duchamp's dream of audience engagement, but in ways that revealed new layers of absurdity, echoing the very questions he raised about the nature of art, authorship, and value.

Tristan Tzara’s Dada Manifesto

Finally, let’s revisit Tristan Tzara’s manifesto written in 1918; This manifesto was a foundational text for the Dada movement, encapsulating its anti-establishment, anti-rationalist ethos. This text disintegrates meaning with each line, where the goal was to make sense of a senseless world. Tzara argued against traditional art, against sense itself. “Dada” was born of disillusionment with meaning, and one hundered years later, in the 2020s, the disillusionment of reality reigned supreme. The “Techno-Modernist” age was one where truth was a slippery concept—propaganda, misinformation, fake news, and endless conspiracy theories were the norm.

Just as Tzara mocked the sanctity of language and truth, younger generations during the 2020s, particularly Generational Z or Generation Zoomers (those born from 1997 to 2012) mocked the sanctity of meaning, reality and making sense. We can see this in an example by Gen Z artist Ebian Selcerk, in their Clown Manifesto written in 2026: “No cap: the world’s a dumpster fire, burning in the cold light of clout. Systems on systems, super sketch, all sus and ready to fall—trust nothing, not even the algorithm. The billionaires scream “Save!” but only hoard pixels piling higher, an empire of digital dust. We are tired, ghosting normalcy, vibing on chaos as the planet sways beneath us, big yikes, fr. Let this be our generation’s manifesto: we stan the absurd, we remix the trash, we clown the rulers, we live and laugh in the ruins—bet.”

Every person, every moment was a remix, a collage of projections. Reality, they realized, wasn’t just fake—it was both “real” and “unreal,” certain and meaningless all at once. As Tzara once said, “Logic is a complication. Logic is always wrong. It draws the threads of notions, words, in their formal exterior, toward illusory ends and centers. Its chains kill, it is an enormous centipede stifling independence. Married to logic, art would live in incest, swallowing, engulfing its own tail, still part of its own body, fornicating within itself, and passion would become a nightmare tarred with protestantism, a monument, a heap of ponderous gray entrails.” Meaning and truth, in the 2020s, was not a given, but a choice, an absurd negotiation between influencers, politicians, algorithms, the news cycles and everyday people simply trying to make sense of a world rifled by contradictions and chaos. Truth flickered like a faulty neon sign, manipulated by headlines, distorted through the lens of social media, chopped into bite-sized trends and reassembled as memes. Every day, reality was rebranded and resold—filtered, reposted, going viral only to vanish, replaced by something newer, something flashier, something just as empty. People clung to whatever fragments they could, but those fragments were slippery, remixable, open to endless interpretation. This was a world where identity, knowledge, and even morality felt like a shifting collage, a surreal tapestry woven by a thousand invisible hands, each holding a brush, each painting over what came before. As Tzara foresaw, logic’s chains shattered in this fractured age, and from the debris, people pieced together a reality that was less a foundation and more a performance—absurd, beautiful, and terrifyingly fragile.

As we step back and look at the big picture, we see the absurdity that pervaded Techno-Modernism was, in fact, a weapon against the control and commodification of life. The techno-modernist artists resisted the pressure to conform to “data-driven” behavior. Many, such, as those in the generations following Gen Z, those who came to be known as Generation Alpha, began to distance themselves from technology, and thus we had a rise, once again, of more socially-engaged art that aimed to illuminate the deep fractures in society: houselessness, addiction, trauma, oppression, climate change. Art, in response to technology, the techno-feudalist and neo-fascist states such as those lead by America’s 50th president Elon Musk, along with Generation Z and Generation Alphas existential crisis with climate change, ongoing wars and injustices in the world, moved towards more grassroots initiatives by the mid 2040s/50s where art became a form of radical presence, existing less in the digital realm and more in physical spaces reclaimed by communities. By the mid-2040s/50s, art had become an act of quiet rebellion, a direct counter to the dominance of algorithms and surveillance. Instead of chasing digital validation, artists created for their local communities, crafting works that could be touched, smelled, felt—sensory experiences that defied commodification. These grassroots initiatives were embedded in the real-world struggles of the people: murals that told the stories of neighbourhoods displaced by climate change, installations in abandoned warehouses highlighting addiction and trauma, and performances in public parks that reimagined collective healing. In those years after techno-modernism, art served as both a mirror and an alleviant for society’s wounds, challenging techno-feudal control by rooting itself in tangible, lived experience, restoring art as an instrument of liberation and human connection.

In conclusion, Techno-Modernism of the 2020s repeated much of the same patterns observed in the early 1920s —an era of art that danced between reality and illusion, driven by a skepticism toward meaning, a distrust of authority, and a will to make absurdity an act of resistance. The phallic rockets, the endless scrolling, the likes, and the propaganda—all of it was both surreal and deeply political.

So, what have we learned from Techno-Modernism of the early 20th century? Perhaps it is that we must confront the absurdity of our time, question the structures around us, and, as Duchamp, Heartfield, and Tzara did, and later on the artist of Generaation Z and Alpha, we must embrace absurdity as a form of protest and liberation. These artists, although separated by 100 years, taught us that art can dismantle oppressive structures, not by following the logic imposed by those in power but by defying it, mocking it, and exposing its hollowness. Techno-Modernism revealed that meaning is fragile, truth malleable, and reality often distorted by those who hold the tools of control. In a world where the commodification of identity and experience threatens to stifle individuality, art stands as a reminder of our capacity to reclaim meaning, to reconnect with each other, and to turn resistance into a creative, radical act.

As we reflect on the absurdity and rebellion of the past, we realize that the next 100 years depends on the courage to question, to laugh, and to build new spaces of connection. Techno-Modernism’s legacy urges us to confront our time with curiosity and defiance, reminding us that in a world increasingly dictated by algorithms, data points and artificial intelligence, art’s greatest power lies in its ability to make us human, fully engaged, and fearlessly present.

In 2016, Donald Trump won the U.S. presidential election, a seismic event that exposed the fractured reality of the early 21st century. This victory signaled not only a shift in political power but also the resurfacing of historical tensions, traumas, and ideologies many thought were left in the past. Now, having won the 2024 U.S. presidential election, Trump returns to office for a second term. For many, including myself, his victory serves as a painful reminder of unresolved histories and latent biases that still haunt our families, our bodies, and our societies. The truth of our current reality is not merely political; it is visceral—deeply embedded in generations of trauma, inherited beliefs, and a globalized world struggling to reconcile with itself. It compels me to confront my own family's past and present views, tracing back to the fascist regime my parents fled in Portugal, only to encounter a new set of challenges, contradictions, and injustices here in Canada.

My parents emigrated from Portugal in the 1960s to escape the grip of fascism, hoping to find a better life on Canada’s shores. Like many Portuguese immigrants of that time, they were greeted with prejudice and suspicion, often grouped with Italians, Spanish, and Greek newcomers who were seen as threats to “white” Canadians’ job security and economic resources. (1) Despite this, Canada granted them a kind of freedom—a freedom they believed would offer safety, security, and a future free from oppression. Yet, as I look at my family today, I find myself caught in a web of irony. My mother recently revealed to me that she supports Trump, a figure whose rhetoric fuels division and resentment; my father and brother, despite their own experiences with discrimination, make unconscious and casual racist remarks about BIPOC individuals. The very liberty and safety my family sought seems undermined by their adoption of the same biases they once feared. Meanwhile, the women in my family, whose autonomy was limited during the fascist era of Portugal, have internalized a worldview that denies others the freedom to choose for themselves: my mother is pro-life, and my aunt believes that trans children are somehow “sick.” This painful contradiction reveals the complexity of generational trauma and how systems of oppression reassert themselves even across borders and decades.

Lisbon on the 25th April 1974; ending 40 years of fascism under the rule of Dr. Salazar (Hemeroteca Digital)

These patterns are not unique to my family. Trauma lives in our bodies, influencing how we think, behave, and view the world. Like so many men of his generation, my father was the “dictator” of our household. His authority ruled our lives, and as children, we internalized his control and adopted his biases. My mother, in her own way, mirrored the patriarchy she had been subjected to, a system she had learned to navigate and survive. This dynamic wasn’t just evident in our family; it played out in households everywhere. Boys grow up seeing dominance and violence—whether physical or emotional—as a normal, even legitimate, expression of power. They were denied the space to be vulnerable, to develop empathy or emotional intelligence. Anger and violence were the only models available, reinforced not just at home but in schoolyards, in the media, and throughout society. (2) Our family’s internalized power dynamics reflect broader societal structures, ones that favor domination over empathy and authority over compassion. These structures, embedded in family norms, continue to shape our identities and influence how we relate to the world.

The pain held by men often extends outward, leading to violence that hurts not only others but themselves. Hurt men hurt others, perpetuating cycles of aggression that ripple across communities and even nations. This dynamic resonates far beyond my personal experience, echoing in the ongoing conflicts and hostilities that shape our world. The current conflict between Israel and its Arab neighbours, for example, is arguably rooted in Jewish trauma stemming from the Holocaust, a historic atrocity that has left a legacy of fear, distrust, and defensiveness. (3) This is a painful truth across humanity: unresolved trauma fuels cycles of harm, affecting entire generations and communities. Our collective pain, if left unaddressed, compels us to recreate the suffering we’ve endured rather than heal from it.

History is indeed repeating itself. I remember a teacher once telling me that history is “a study of the past to understand our present and prepare for the future.” Looking back, it’s clear that today’s reality bears troubling resemblances to the early 20th century. Back then, societies worldwide faced the Spanish flu pandemic, economic challenges, rapid technological advances, and waves of immigration. (4) The resulting tensions created fertile ground for fascism to flourish in Europe. Now, in the early 21st century, we find ourselves navigating similar dynamics—public health crises, economic uncertainty, demographic shifts, and social polarization. The same unresolved fears, biases, and traumas that once led to fascist regimes are reemerging, hinting at the dangers of ignoring history’s lessons.

The trauma my family carries is a microcosm of this cyclical history—a legacy of forgetting, of willful ignorance, of failing to address past wounds. Hurt people continue to hurt people, passing down their unresolved pain in forms that may seem contradictory or hypocritical to outsiders. My family’s prejudices and fears, birthed from their own suffering and challenges, seem almost surreal at times, an irony that reflects a broader societal hypocrisy. We repeat destructive patterns not because we are incapable of change but because we have failed to truly confront and understand the traumas underlying these behaviors.

Since recent Trump’s election, I have felt this reality deeply within my own body. Some mornings, I wake up frozen, immobilized by the weight of the world’s present challenges. I think about the people suffering in this neo-fascist era, about the loss of freedoms and the pervasive trauma left unresolved across generations. This immobilizing anxiety, I realize, is not just a response to present events but a reminder of the unresolved traumas of the past—a call to confront the unresolved pain inherited from those who came before us.

Reality today requires acknowledging the return of neo-fascism, a painful reminder that history can indeed repeat itself. But in this acknowledgment, there is also an invitation: to make space for grief, to reconnect with our bodies and the histories they carry, to confront both personal and societal trauma. This requires courage—the courage to see the good and the bad within ourselves and others, to recognize the complexity of every individual, and to embrace the diverse ecosystems that make up our world. To return to our bodies, the land, and art that offers healing and medicine for the soul. To continue fighting against injustice, not just in action but in understanding. And, most importantly, to cultivate empathy for those who are different from us—those who are impacted in ways we may never fully comprehend by the systems we live within.

This is our reality. It is complex, painful, and challenging. But it is also an opportunity to transform trauma into understanding, division into compassion, and fear into an acknowledgement of the past, a deeper connection with our bodies, with each other and our shared world.

(1) Ari, Esra; Portuguese-Canadians as "Dark-Whites:" Dynamics of Social Class, Ethnicity, and Racialization through Historical and Critical Analysis; https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA693325858&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=10571515&p=IFME&sw=w&userGroupName=anon%7Eff1363c2&aty=open-web-entry

(2) hooks, bell. The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love. Washington Square Press, 2004.

(3) van de Kerk, Bessel and Stern, Jessica; POV: The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict and the Psychology of Trauma; https://www.bu.edu/articles/2024/the-israeli-palestinian-conflict-and-the-psychology-of-trauma/

(4) Funke, Manuel, Moritz Schularick, and Christoph Trebesch. "Defensive Nationalism: Explaining the Rise of Populism and Fascism in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries." Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, Oxford University Press, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.993.